Level 1: Fat loss hacks!?!? 10 charts show why you don’t need them.

Just over 20 years ago, Google was a garage startup, and no one had heard of “fat loss hacks.”

But a lot can change in two decades. (We’ll spare you the screenshot of our search results.)

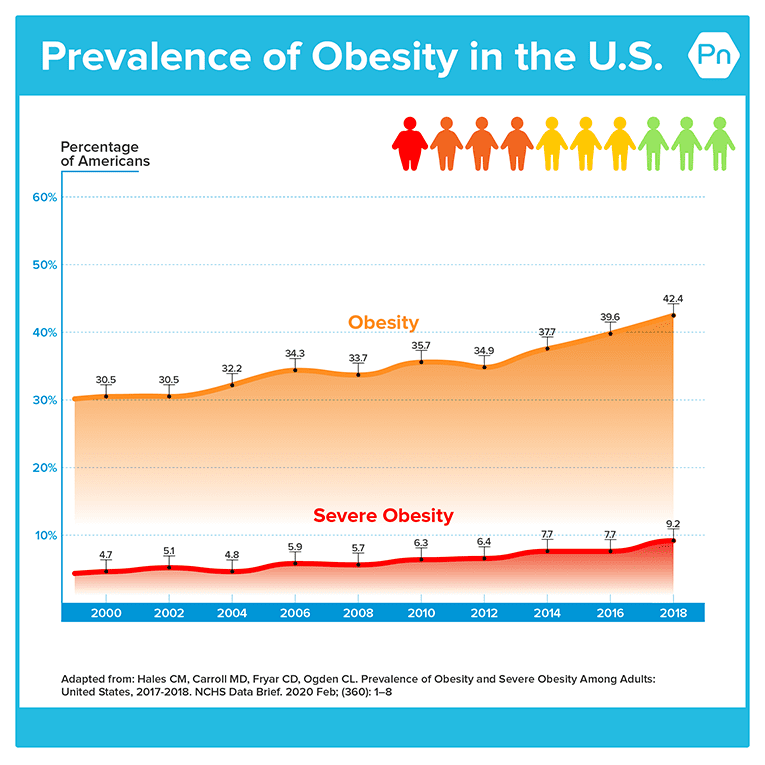

One thing that hasn’t changed: Obesity is still on the rise.1

Which is to say:

There are no legitimate fat loss hacks—despite server farms filled with fat loss hacks.

That’s because obesity isn’t a simple, hackable problem.

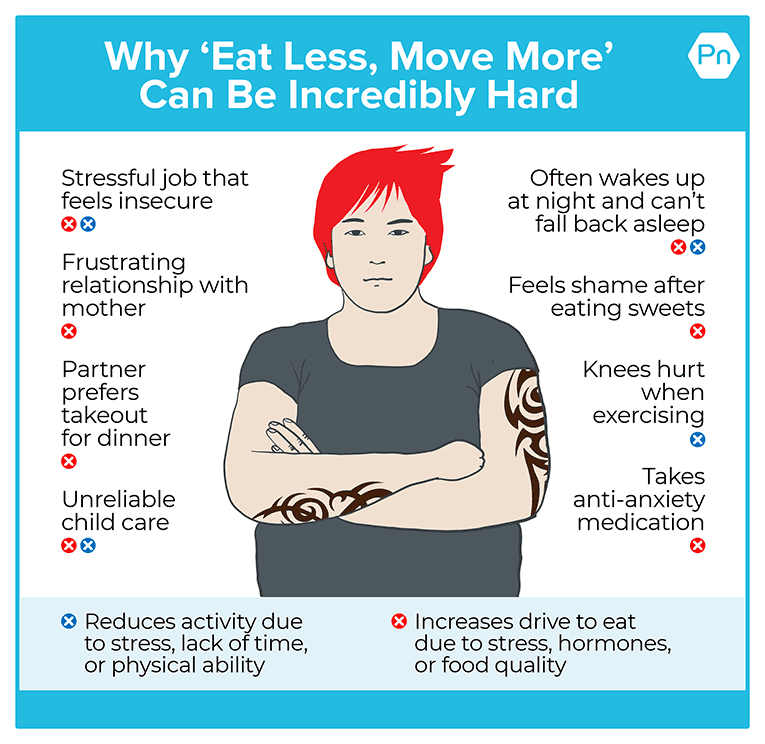

There are many interconnected factors—physical, psychological, social, environmental, emotional—that influence our ability to eat less and move more.

And the magnitude of each factor can vary for any given individual. For a visual, check out the illustration below.

Now here’s the ironic part:

Most “diet hacks,” “fast fixes,” and “easy solutions” make fat loss even harder than it needs to be.

These approaches often promote overly restrictive and unnecessary rules that:

- eliminate carbs or sugar

- demonize fat or meat (ethical reasons aside)

- moralize food choices (implying there’s a “right” and “wrong” way to eat)

- encourage or require dietary perfection

- emphasize what’s theoretically optimal over what’s truly practical (and may advise supplements or “superfoods” as necessary components)

This isn’t to suggest food and exercise choices don’t matter. But rather to say: Compared to most fat loss hacks, you (or your clients) can enjoy greater flexibility in what you eat and how you exercise—and still get the lasting results you want.

Our case? The 10 charts that follow, labeled Exhibits A-J. When it comes to fat loss, they may help you picture a more effective and sustainable solution—no “hacks” necessary.

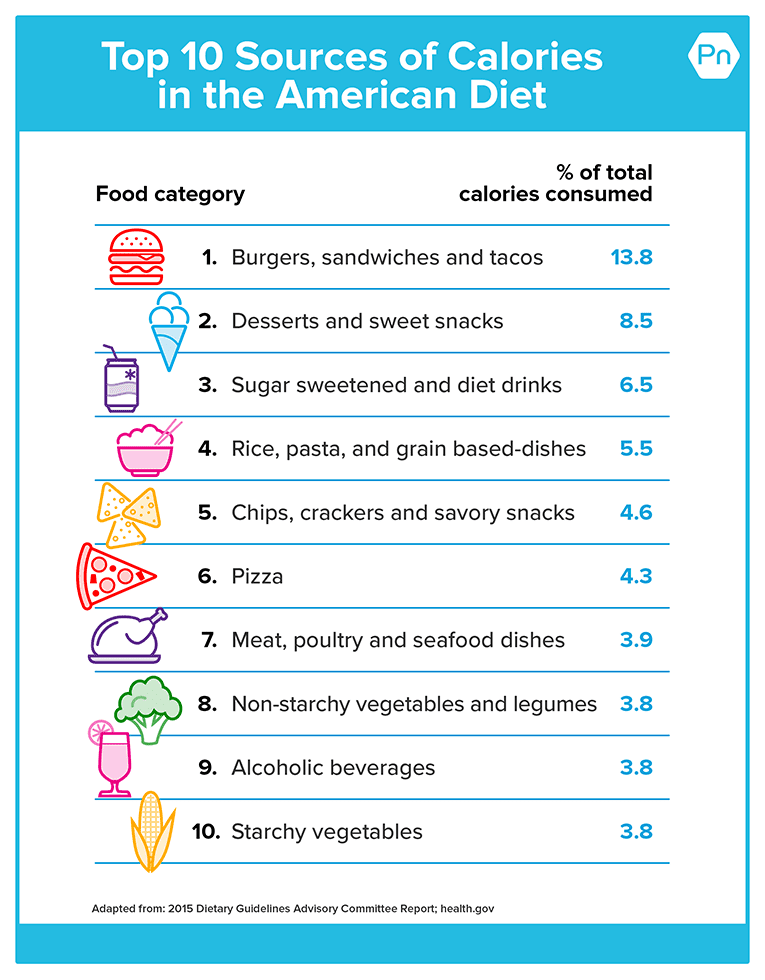

Exhibit A: The foods we eat the most.

There’s no doubt: Many people who struggle with weight control eat too many carbs. (And too much fat.) But is this an indictment of the carbs themselves? Or the sources of those carbs? Consider this data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).2

Based on this research, nearly one-quarter of the average American’s calorie intake comes from desserts, candy, snacks, and sugary drinks. (Not all foods are shown in the chart.)

That’s a good chunk of daily calories.

These foods aren’t on anyone’s recommended eating list. But as you can probably see: Drastically cut carbs—or even just sugar—and you’ll automatically eliminate most of these “junk foods.” (And, importantly, lots of calories from both carbs and fat.)

This leads to a popular claim: When you give up carbs, you stop craving junk food, making it easier to lose fat.

Which may indeed be true. But is this because you’ve eliminated the carbs, or because you’ve eliminated the junk food?

Our next chart provides some insight.

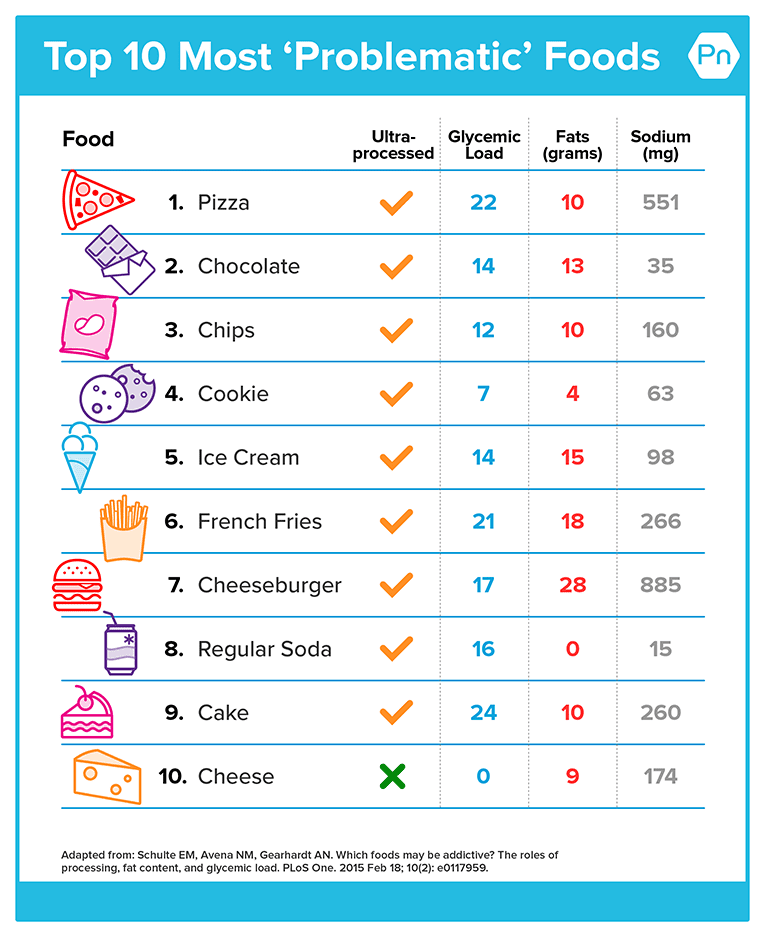

Exhibit B: The delicious foods we can’t resist.

In a recent study, University of Michigan researchers looked at the “addictive” qualities of common foods.3 The chart below shows the 10 foods that people are most likely to rate as “problematic,” using the Yale Food Addiction Scale.

Whether you restrict carbs or fat, nine out of 10 of these foods would be off-limits—or at least significantly reduced.

Note that all but one are ultra-processed foods, and most contain some combination of sugar, fat, and salt.

This ingredient combo makes these foods “hyper-palatable”—or so delicious they’re hard to stop eating. Food manufacturers engineer them to be this way. (Learn more: Manufactured deliciousness: Why you can’t stop overeating.)

What about the foods, such as soda or chocolate, that aren’t loaded with all three of those ingredients? They tend to contain “drug-like” compounds—such as caffeine and/or theobromine—to enhance their appeal.

With this in mind, It’s worth taking a look back at the previous chart, too. Eight out of 10 of the most “addictive” foods shown here in Exhibit B are also five out of the top six most consumed categories of foods in Exhibit A.

What do they have in common? They’re usually ultra-processed and manufactured to be irresistible.

Now consider: What foods are especially problematic for you? And what do they have in common?

(To test this on yourself or with a client, download our Yale Food Addiction Scale worksheet.)

Typically, minimally-processed, whole foods like vegetables, fruit, beans, and whole grains aren’t high on many people’s “problem” lists. We simply don’t tend to overeat these foods consistently.

Yet there are fat loss hacks that tell you to avoid fruit, never eat a starchy vegetable, and eschew beans and grains of any kind.

Our question: When exactly did these foods become the problem?

Which brings us to our next item.

Exhibits C-G: The nutritious foods we aren’t eating.

Public health officials have long advised we eat more vegetables, fruit, legumes, and whole grains.

But these recommendations have come under fire for not working. Because collectively, we’ve gotten fatter despite them. The argument from certain camps: It’s the fault of these “healthy” foods.

Is that the case, though?

Or is it because people are eating other (ultra-processed, hyper-palatable) foods instead?

If that sounds like a loaded question, here’s why:

According to NHANES data, 58.5 percent of all calories consumed in the US come from ultra-processed foods.4

And our consumption habits aren’t improving: During the five-year survey period, that percentage increased by one percent every year.

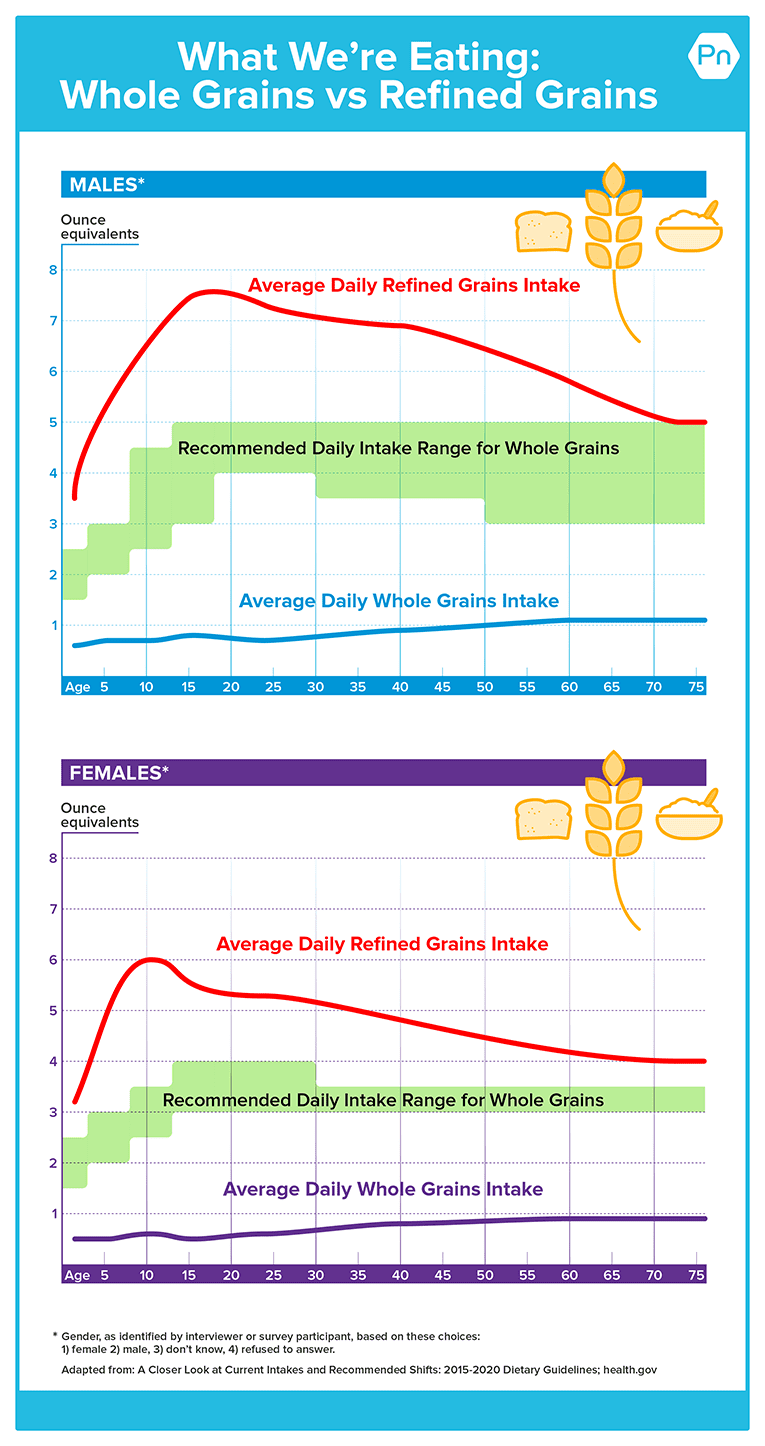

But let’s take a closer look at the recommended “health” foods, starting with whole grains, since they’re often particularly vilified.

Given this NHANES data, you can certainly argue people eat too many refined, ultra-processed grains.5

But whole grains? Comparatively speaking, people still aren’t eating them.

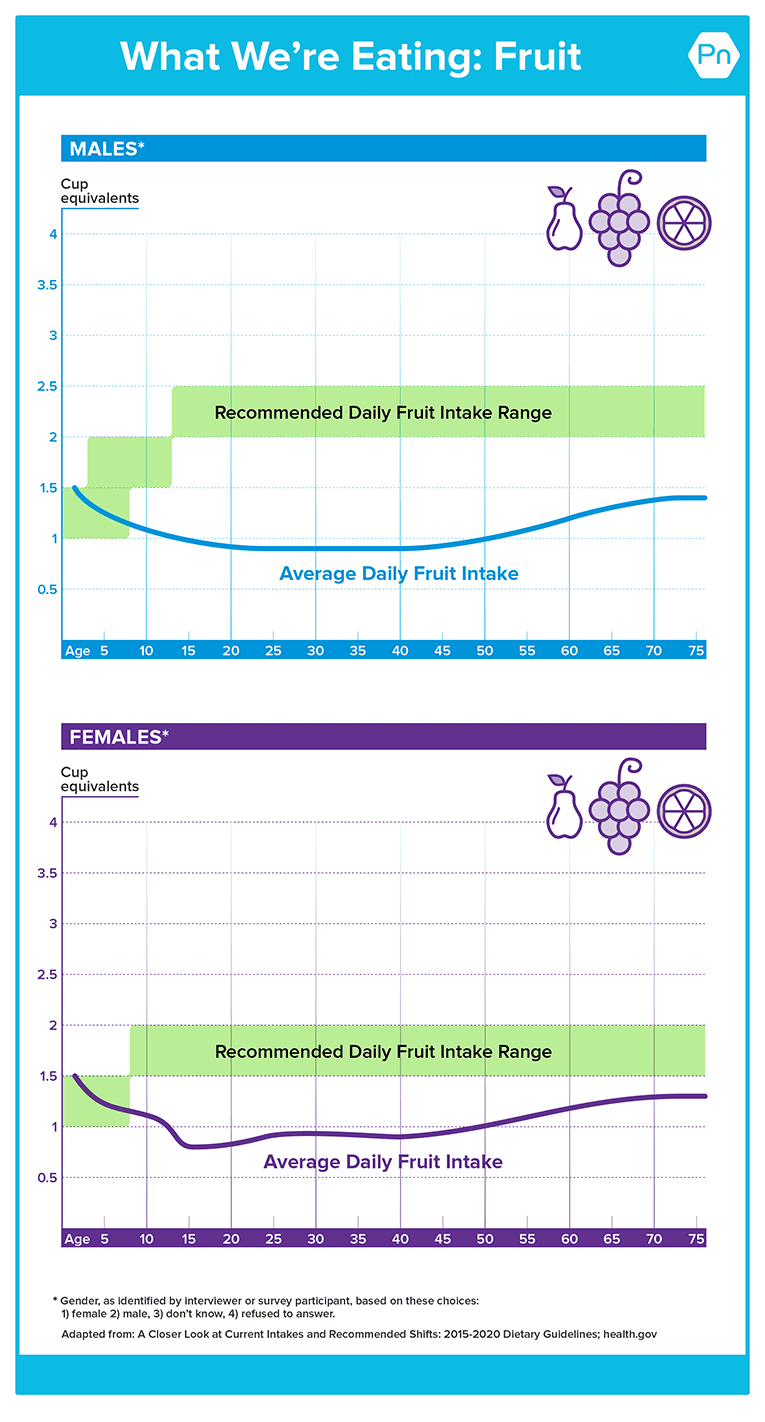

The same is true for fruit.5

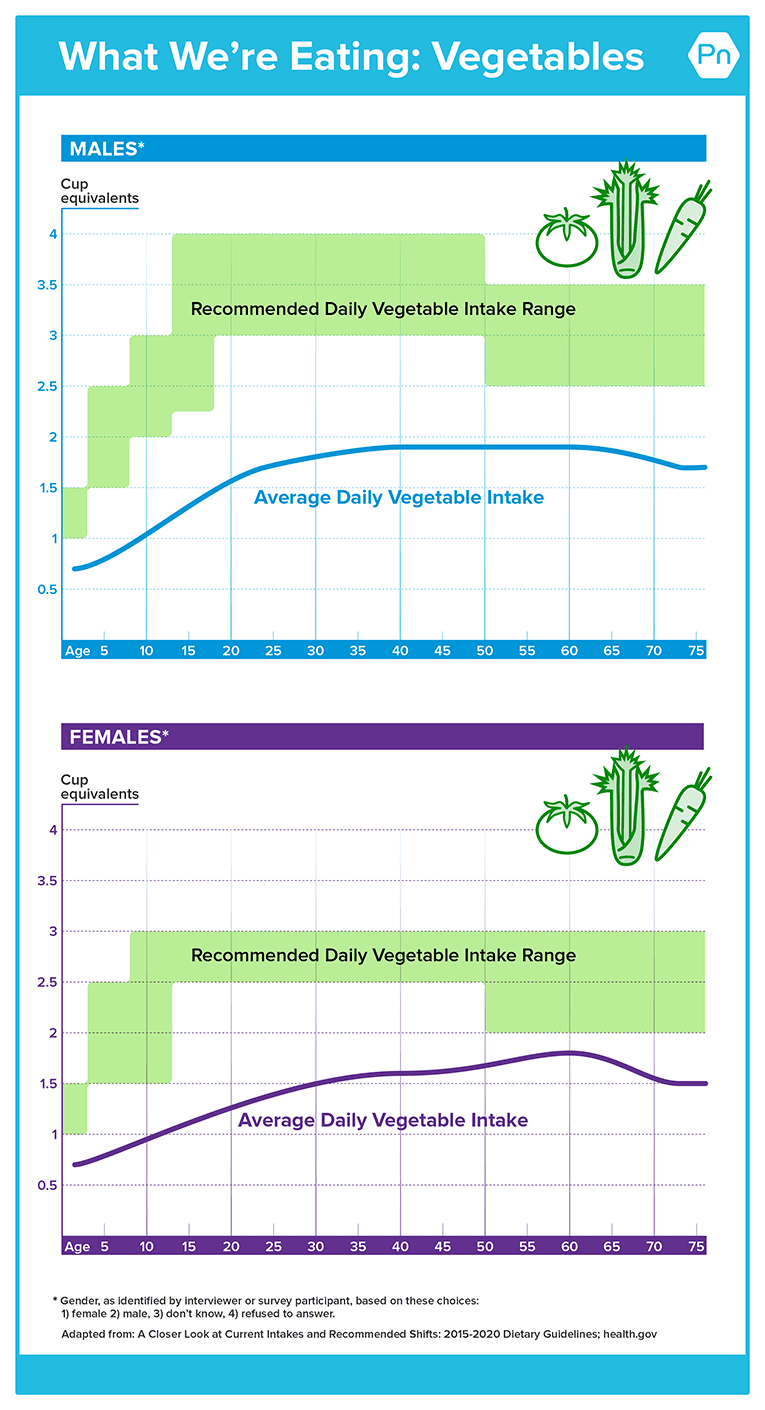

And vegetables.5

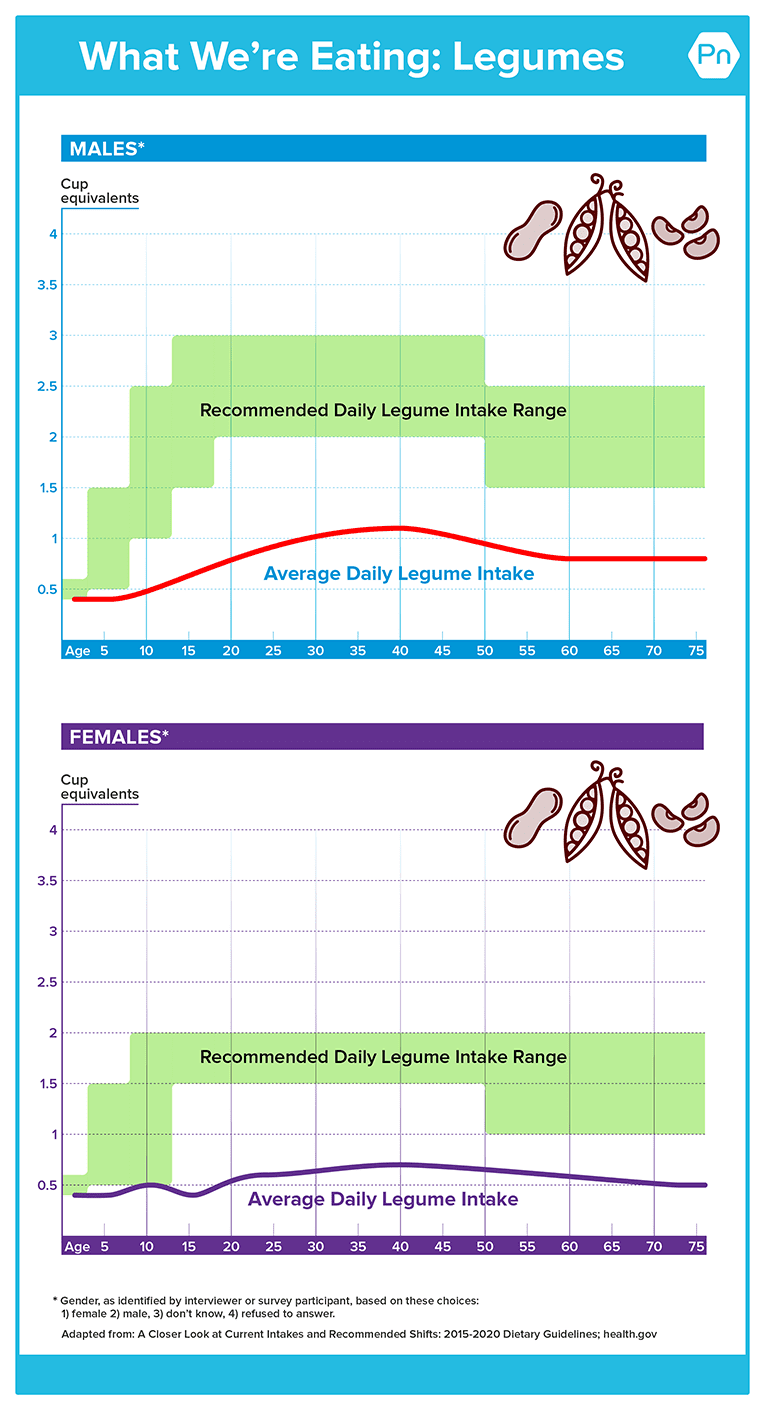

And legumes.5

The reality is this: When looking to improve their diet, most people focus on subtraction. They might say: “I’m giving up sugar” (see Exhibit A) or “I’m cutting out junk food” (see Exhibit B).

Trouble is, there’s often no plan for what they’ll eat instead. This can lead to feelings of deprivation and diet dissatisfaction.

That’s why it can help to start with addition: Eat more vegetables. Eat more fruit. Eat more whole grains and legumes. Eat more lean protein. (Men tend to consume fattier sources of protein, which provide more calories, and women often struggle with getting enough protein overall.)

Based on our experience working with over 100,000 clients, this “add first” strategy can be highly effective at “crowding out” ultra-processed, hyper-palatable foods. (No, this doesn’t mean you have to live life without any “junk food”: Learn why.)

Besides getting more nutritious foods into your diet, something else often happens when you “add first”: You automatically eat less.

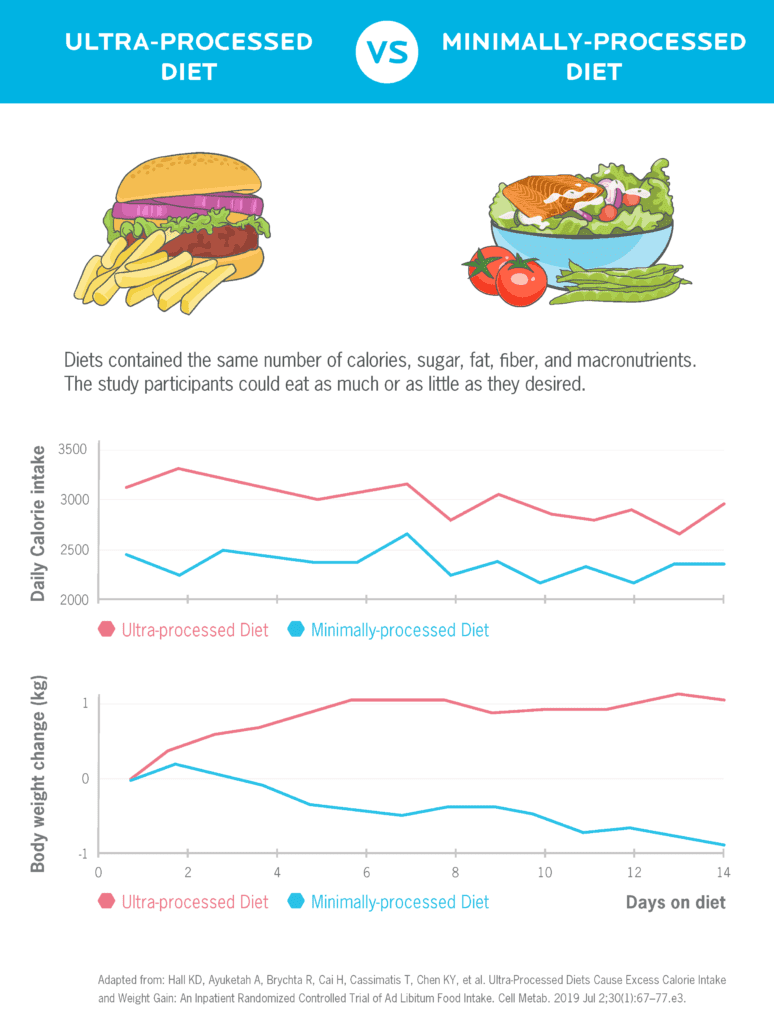

An example: A recent study conducted at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (an institute of the NIH).6

Twenty adults were admitted to a metabolic ward and randomized to a diet of ultra-processed foods or minimally-processed foods. They were allowed to consume as much or as little as desired. After two weeks, they switched and did the alternative diet for two weeks.

The result: As you can see in the chart below, participants ate 508 more Calories per day and gained weight on the ultra-processed diet. They lost weight on the minimally-processed diet.

It’s a small but very well-controlled study (other studies have shown similar outcomes7,8), and it reflects what we often see with clients who use our “add first” approach.

Their overall calorie intake goes down as they include more minimally-processed foods in their diet. They find food more fulfilling and satisfying.

If it seems counter to conventional wisdom to add versus subtract, you might ask yourself: What if conventional wisdom is wrong?

You’ll undoubtedly find that adding first is far easier than overhauling your diet instantly. And if it’s not working for you, you always have the option to subtract.

But the best part: It doesn’t require perfection to drive meaningful results, as you’ll see in Exhibit H.

Exhibit H: Progress doesn’t require perfection.

When we coach clients at Precision Nutrition, we don’t expect them to change their habits or build new skills overnight. We don’t even want them to try.

Instead, we give them one daily health habit to practice—such as consuming five daily servings of fruit and vegetables or eating lean protein at each meal—every two weeks for 12 months.

These practices accumulate, and by the end of the year, they’re incorporating 25 practices total.

This is how we help folks develop healthy eating and lifestyle skills and habits that become automatic—and aren’t reliant on discipline and willpower.

None of these practices direct clients to avoid certain foods.

That just happens.

But because our clients are humans, it doesn’t happen all the time.

And that’s okay. It works anyway.

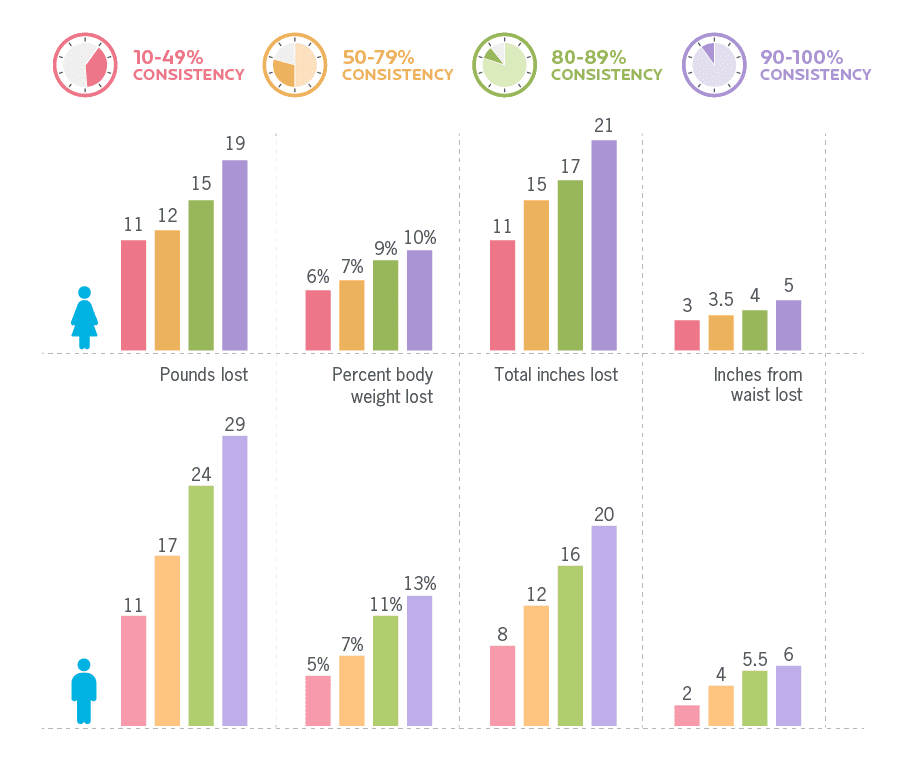

Our data shows when people are 90 percent consistent with their daily practices, the results are usually amazing.

But even when folks are only 50 to 80 percent consistent, they experience profound outcomes.

What’s more, clients who are just 10 to 49 percent consistent can still make significant, meaningful progress.

Here’s what the results look like.

This approach is based on the idea that progress isn’t about perfection.

It’s about accepting that better is better. And that consistent effort, even if small, can translate into meaningful fat loss and health benefits.

That’s not just true when it comes to nutrition. It’s true of exercise, too…

Exhibit I: Movement doesn’t have to be programmed.

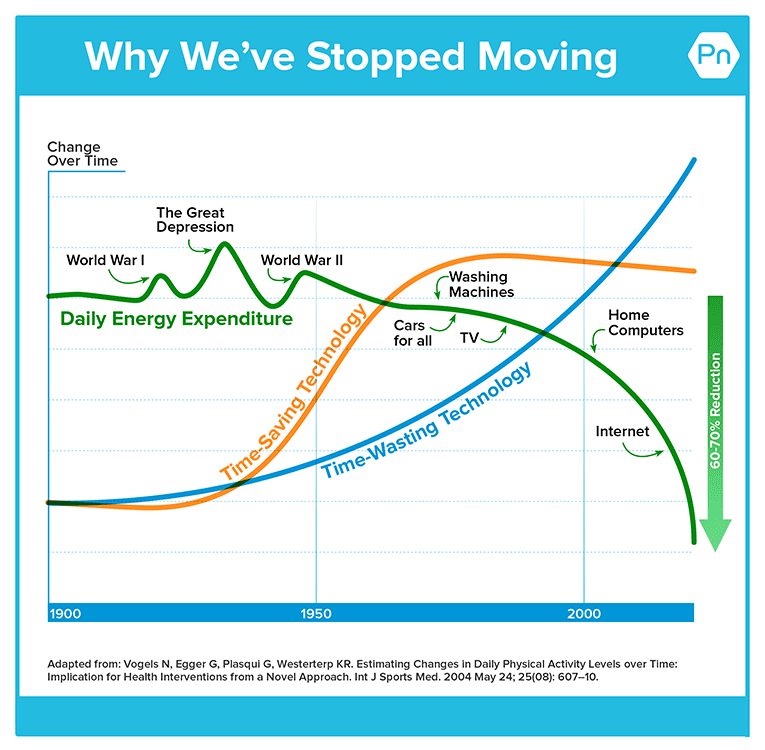

Here’s a fun chart. It tracks the change in daily energy expenditure from 1900 to the early 2000s.9 The researchers also plotted the widespread adoption of both time-saving and time-wasting technology.

The finding: a 60 to 70 percent reduction in total daily energy expenditure over the last century.

In a previous study, the same scientists calculated that actors playing the part of Australian settlers 150 years ago were 1.6 to 2.3 times more active than sedentary modern office workers.10 That’s the equivalent of walking 5 to 10 more miles daily (or around 10,000 to 20,000 steps).

This isn’t to suggest you need to start walking 10 miles a day. It’s to emphasize how much less we move in today’s modern world compared to any other time in human history. And that most of us would benefit from more daily movement of any kind, even if we regularly work out.

Practically-speaking, this might only require a mindset shift. For example:

- Vacuuming the house

- Weeding the yard

- Taking the dog for an extra walk

- Shooting hoops in the driveway

- Marco Polo with the kids (instead of watching them play in the pool)

These aren’t hassles or time drains: They’re opportunities to move a little more while you accomplish other stuff.

No, these activities won’t maximize your per-hour calorie burn. But this slight reframing might inspire you to get more done, have more fun, and increase your daily energy expenditure significantly—all without requiring more time in the gym.

What to do next

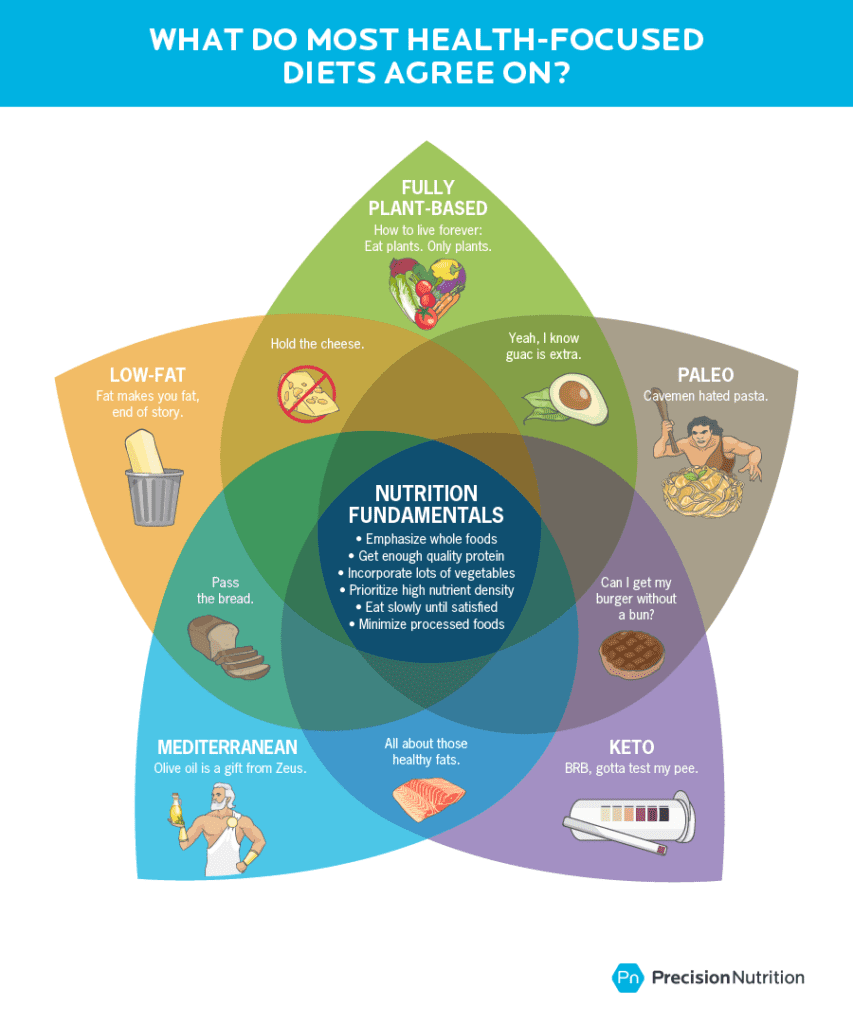

We now present Exhibit J. If you’re a dedicated follower of PN, you may have seen this Venn diagram before. (We like it a lot.)

The upshot? The nutrition fundamentals in the middle of the diagram are universal among almost every well-considered dietary pattern. You might call them the basics.

That doesn’t mean they’re easy. In fact, they can be really hard.

After all, how many people do you know who consistently follow these six nutrition fundamentals?

Or perhaps more appropriately, how likely is the average person to successfully adopt these fundamentals all at once… for the long-term?

The odds aren’t good. You probably don’t need a chart to see that.

Now consider: If the basics are too hard, what can you expect from an approach that restricts even more foods or advises immediate and dramatic changes to what they’re doing now?

Make no mistake: One can do very well on keto, Paleo, fully-plant based, or any other type of diet. But overnight? That doesn’t usually happen, at least not in a way that’s sustainable.

Instead, we offer another approach—one that fosters lasting behavior change.

Here’s the short version of how to start:

Step 1. Focus on just one new daily practice at a time.

Do that for two weeks or three weeks. The idea is to choose a daily practice that helps you make positive progress, no matter how small. You could start with the fundamentals, selecting one of these options:

- Get enough high-quality protein

- Eat lots of produce

- Emphasize minimally-processed whole foods

- Eat slowly until satisfied

(After you’ve practiced one for a couple of weeks, try adding on another.)

Step 2. Make the practice seem easy.

If you’re eating one serving of fruits and vegetables a day now, getting five servings every single day might be too hard.

But could you shoot for three servings a day? Or five servings three or four days a week?

The idea: You want a practice that’s likely to result in success. You can build from there.

Imagine: If you stack easy on top of easy on top of easy, you wake up one day and realize you’ve made serious change, and it was… easier than you expected. (Because we won’t pretend lasting change is ever “easy.”)

Step 3. Chase consistency, not perfection.

Your day won’t always go as you want: a surprise deadline at work, an argument with your partner, an emergency trip to the vet.

But as we’ve already shown, you can see real benefits with less than 50 percent consistency. One day doesn’t negate your positive efforts.

All of this may seem too “basic” to work.

Or you might think, “It sounds way too slow! I need a faster fix!”

That’s completely understandable.

But you might feel this way because:

- You’re accustomed to appealing ads that promise “six-pack abs in six weeks” or a “bikini body in 30 days.”

- Your previous fat loss experiences have made you feel deprived and miserable (and often like a failure).

These two factors are closely related, in case you haven’t made the connection.

Because of this, it’s normal to feel uncomfortable by the “long duration” of behavior change, the lack of a “detailed eating plan,” or the idea of “making just one easy change at a time.”

If that’s the case, we’d simply ask:

How’d the alternative work for you in the past?

If you feel good about the experience and the outcome—and where you are now—maybe you’ve found what works for you.

But if you don’t have the warm, fuzzy feels, it may be time for a new approach (whether that’s for yourself or your clients).

One that helps you transform your eating and lifestyle habits, in a way that takes the full complexity of fat loss (and your whole life) into account.

So that you’re not miserable. You don’t feel deprived. And it’s hard to fail.

Come to think of it, that sounds a lot like a fat loss hack. (But it’s not.)

References

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

If you’re a coach, or you want to be…

Learning how to coach clients, patients, friends, or family members through healthy eating and lifestyle changes—in a way that’s personalized for their unique body, preferences, and lifestyle—is both an art and a science.

If you’d like to learn more about both, consider the Precision Nutrition Level 1 Certification. The next group kicks off shortly.

The post Level 1: Fat loss hacks!?!? 10 charts show why you don’t need them. appeared first on Precision Nutrition.

Nenhum comentário